Preserving and Collecting Mobile Device Data (2025 Update)

Mobile devices are ubiquitous, and so is their use to transmit and store information that could relate to litigation or investigations. Yet litigants frequently overlook mobile device data, partly because many attorneys have a limited understanding of how to treat it in discovery.

This article provides a short overview of mobile device data, what it is, why attorneys should care about it, and how they can develop a defensible discovery plan for mobile device data.

What is Mobile Device Data?

“Mobile device data” describes electronically stored information (“ESI”) on mobile devices (smartphones, tablets, drones, etc.). Mobile device data can be stored in device memory (i.e., memory chip(s) soldered to the device motherboard), a SIM card connected to a device, and digital memory card(s) used to store ESI. Increasingly, data is synchronized between mobile devices and cloud-based platforms, resulting in a complex ecosystem of distributed data storage and management.

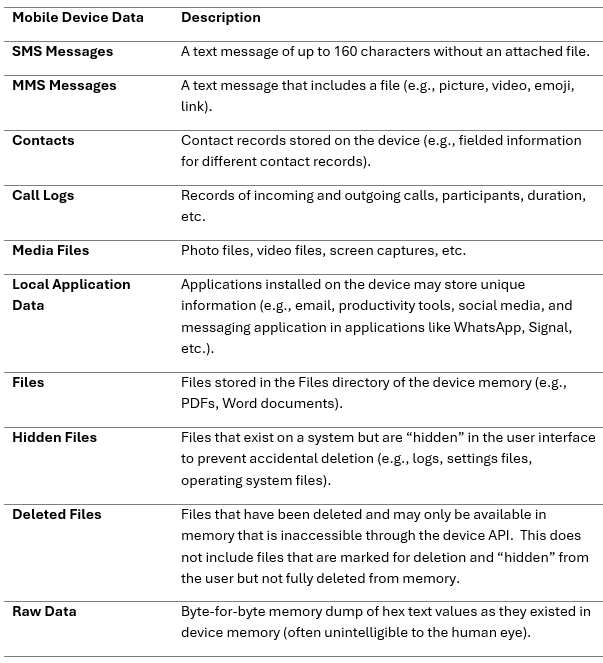

Common types of mobile device data are described in detail in the chart below.

What about Ephemeral Messages?

Mobile messaging applications with “ephemeral messaging” functionality like Signal, Telegram, and WhatsApp have become more common in recent years, and can present unique discovery challenges. Ephemeral messages are communications that are encrypted and, by design, last only a short time, as the applications that are used to send them automatically delete the messages from both the sender’s and the recipient’s mobile devices. As the Sedona Conference noted in its 2021 Commentary on Ephemeral Messaging, ephemeral messaging data is subject to the same duties of reasonable and proportional efforts to preserve as any other form of ESI, assuming there is a duty to preserve, but it also presents unique challenges with prospective preservation. The ephemeral nature of these messages makes them difficult to capture before they disappear, and their encryption complicates extraction and decoding.

Mobile Device Data is a Significant Source of ESI

The explosion of mobile device use is one of the most consequential areas of technological change over the last decade. Researchers estimate that 7 billion smartphone subscriptions existed worldwide in 2023 and forecast that the number will climb close to 8 billion by 2028. (See Federica Laricchia, Smartphones - statistics & facts, Statistica (June 12, 2024), https://www.statista.com/topics/840/smartphones/#topicOverview). The number of mobile devices and users continues to increase, and evidence suggests that mobile devices are supplanting personal computers and laptops as primary computing devices. Pew Research estimates that 98% of Americans now own a mobile phone and 15% use a smartphone exclusively to access the internet. (See Mobile Fact Sheet, Pew Research Center (Nov. 13, 2024), https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/).

New innovations continue to change the way mobile devices use and store data. This presents challenges for discovery as the ability to access and extract mobile device data varies greatly depending on device hardware, software, operating system, encryption, and chipset.

Mobile Device Data is a Significant Discovery Issue

While the mobile data technology and use landscape is constantly changing, the impact on eDiscovery is not. As the Sedona Conference observed in its Commentary on BYOD: Principles and Guidance for Developing Policies and Meeting Discovery Obligations, parties “cannot ignore their discovery obligations merely because the ESI is on a device that is mobile[.]”

The legal industry has been somewhat slow to recognize the importance of mobile device data, and some attorneys still treat mobile data as presumptively “off the table” in discovery, without having thoroughly considered the role of such data in each case. Where parties and their counsel do take some steps to preserve or collect mobile device data, those steps can be incomplete, and relevant data may be lost. The result has been a stream of judicial decisions sanctioning parties and their lawyers for having failed to reasonably preserve and produce mobile device data.

A few examples from 2024 highlight this recurring issue:

- In Jones v. Riot Hospitality Group, LLC, 95 F.4th 730 (9th Cir. 2024), the Ninth Circuit affirmed an Arizona district court’s dismissal of a Title VII lawsuit as a sanction for the plaintiff’s deletion of text messages she had sent to friends about the case while it was pending.

- In Cap. Senior Living, Inc. v. Barnhiser, 713 F. Supp. 3d 407 (N.D. Ohio 2024), a federal judge in Ohio found that an adverse inference jury instruction was an appropriate sanction where the defendant continued her usual practice of deleting text messages even after receiving a litigation hold letter. The court held that the “deletions may, or may not, have been made in bad faith, but they were nonetheless purposeful.”

- In Goldstein v. Denner, No. 2020-1061-JTL, 2024 WL 303638 (Del. Ch. Jan. 26, 2024), the Delaware Court of Chancery sanctioned a party for failing to suspend automatic deletion functions on the personal phones of two senior executives, rejecting the argument that preservation was unnecessary because texting was contrary to company policy.

The lesson from these cases and others like them is not that a litigant must capture and produce every bit of data from every custodian’s mobile phone in every matter. Rather, attorneys should carefully evaluate what reasonable steps their clients reasonably can take to preserve mobile device data considering the specific circumstances of their case. Attorneys should familiarize themselves with the available options for preservation and collection so they can select the ones that are right for their matter.

Methods for Preserving Mobile Device Data

Options for preserving mobile device data include:

- Notifying custodians about their obligations to preserve (and instruct them to preserve) information relevant to litigation or investigations stored on their mobile devices. This action is a baseline preservation effort, but it may still be (and often is) reasonable. Depending on the circumstances, however, courts may expect litigants to take additional steps to preserve information beyond relying on each custodian to preserve their own information in place.

- Proactively capturing and preserving copies of broad categories of mobile device data with a purpose-built application (e.g., journaling all SMS or WhatsApp messages sent and received to/from mobile devices and storing those messages in an archive). This action is a more robust option that may help avoid the need to preserve and collect information stored on individual mobile devices, but it will likely require substantial capital and investigation to implement and maintain—and likely will preserve far more information than is necessary.

- Targeted collection of relevant mobile device data is also a preservation option. Depending on the matter, one of the extraction methods described below can be used to preserve information.

Methods for Extracting Data from Mobile Devices

There are multiple methods for extracting ESI from mobile devices, with the feasibility of each varying based on the make, model, and operating system of the mobile device. No one technology can access and extract all data from all mobile devices, and no one type of extraction has guaranteed success.

Methods to extract ESI from mobile devices include:

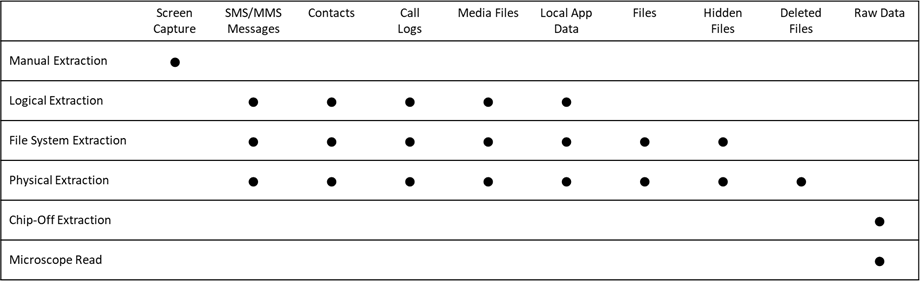

- Manual Extraction methods access data through the device interface and manually capture copies of the ESI (e.g., creating screen captures or recordings, or filming the device screen during the investigation). While this may be the easiest approach and might be appropriate in some matters involving a small volume of ESI where metadata and searchable text are not needed, it may become impractical as the number of devices and the volume of ESI increase. Because this method does not yield searchable text, does not preserve or extract metadata, and may present admissibility challenges, it will not be a viable option in most circumstances.

- Logical Extraction methods utilize forensic software that interacts with the mobile device operating system through an application programming interface (“API”) and extracts only active data that is accessible through the API. This method extracts most live data (e.g., SMS/MMS messages, contacts, call logs, media files, and local application data), and it is the fastest and most widely supported “forensic” collection method.

- File System Extraction methods utilize forensic software to access data on the device without an API and extract all files present in the internal memory, including those inaccessible through the API. This method extracts all files from device storage, including logs and system files, that may not normally be visible to a user. This method requires access to the root storage and thus takes longer than logical extraction.

- Physical Extraction methods utilize forensic software and full access to the internal memory of the mobile device. A physical extraction performs a bit-by-bit copy of the device’s memory. This option is the most comprehensive extraction method. It will copy deleted files and fragments that would not be included in a logical or file system extraction.

- Hardware Forensics methods, such as chip-off extraction and microscope reading, utilize specialized software and hardware to inspect the physical components of a mobile device to identify and extract data. These extraordinarily complex, time-consuming, and expensive methods would only be utilized in the most extreme and narrow circumstances.

What about Remote Collection Options?

When faced with an urgent need to simultaneously collect data from numerous mobile devices spread across multiple geographic locations, litigants are increasingly interested in remote collection of mobile device data. Remote collection refers to the process of gathering data from mobile devices without the need for physical access to the device. This method leverages specialized software and secure connections to extract targeted information directly from the device or cloud storage. One examiner can collect data from multiple locations on the same day, avoiding expensive travel and logistical delays.

Remote collection ensures data integrity and accessibility by preventing potential hardware issues and simplifying the preservation process. It is appropriate and reasonable for situations where quick access to specific data is needed, such as compliance checks, preliminary investigations, or discovery matters where relevant messages just need to be collected, reviewed, and produced in discovery. More robust data extraction is preferable, however, in cases involving criminal investigations, when there is a need to recover deleted data, or when performing a comprehensive analysis of the device is required.

What about Physical Device Preservation?

After extracting the requested information from a mobile device, the question arises whether to preserve the physical device or to return it to the custodian, reset it, reprovision it, or recycle it. Generally, preserving the physical device after data extraction is impractical and burdensome, and will often be unnecessary. It is usually sufficient, assuming the collection method is well documented, to preserve only the collected data, especially when using forensic applications to create advanced logical images or full file system extractions.

There may be cases, however, where extraction of the data alone is not enough. One such situation is where prospective preservation is necessary (i.e., continuing to preserve new messages sent or received during the pendency of the case). Other situations where preservation of the physical device may be critical may include criminal matters, situations in which there are specific questions about the device, or other circumstances where there is some unusual sensitivity around its preservation. Every case is unique, and counsel should carefully consider the preservation obligations and interests particular to each case. But in ordinary civil litigation matters there will often be few reasons to keep the physical device after collection. Preserving data through extraction also ensures future accessibility and avoids hardware, software, security, lost passwords, or synchronization issues that may complicate future access.

Conclusion

As mobile device usage continues to increase, such that they have become a primary means for working and communicating, and the tools and options for the preservation and collection of mobile data become more sophisticated, attorneys should not treat mobile data as an afterthought. While the preservation and collection approaches selected can and should vary in different cases, counsel should always be prepared to:

- Familiarize themselves with available preservation and collection methods, tools, and technologies, including what categories of data are preserved or collected by each option.

- Conduct a reasonable inquiry as early as possible in the litigation to determine:

- What, if any, mobile data is within a client’s possession, custody, or control—taking into account both the legal standard in the relevant jurisdiction and the client’s device usage policies;

- The likelihood that mobile device data is both relevant and unique (i.e., it does not exist in other accessible sources in the party’s possession, custody, or control);

- The importance to the issues in the case of any relevant, unique mobile data; and

- The burden or difficulty of collecting mobile data—including complications such as privacy restrictions on accessing personal devices.

- Choose what methods of preservation and/or collection are appropriate and defensible in light of the circumstances of the case (e.g., data on the phone of a central figure may be treated differently than that of ancillary custodians; collection for a criminal case may be different than for a civil case).

- Consider negotiating with the opposing party a reciprocal discovery approach that applies to both parties’ mobile data.

Counsel may be well served to obtain the assistance of knowledgeable and experienced eDiscovery counsel or consultants to help navigate the complex legal and technical issues that arise in connection with the preservation and collection of mobile device data.