As eDiscovery practitioners cautiously resume in-person conferences and social gatherings, one topic is dominating conversations: the discovery challenges posed by “modern attachments” within the Microsoft 365 (“M365”) environment. A dearth of jurisprudence and little practical guidance is available on this topic; yet the technology continues to rapidly evolve. We prepared this series of articles to provide guidance to discovery practitioners, in-house counsel, and service providers.

One of the foremost issues raised by this evolving technology is whether litigants can, should, or perhaps even must treat “modern attachments” like traditional email attachments. Historically, email attachments have been considered part of an email “family” in discovery because they are actually part of the .msg email file. With “modern attachments,” however, the “attached” files are not part of the underlying message file; no “family” exists in the traditional sense. Litigants and their counsel are weighing any benefits against the risks and burdens associated with treating these documents like traditional email attachments for discovery purposes, where no such “family” relationship exists in the files as they are maintained in the ordinary course of business.

In this first article, we explain what “modern attachments” are and why they are keeping eDiscovery practitioners up at night. We will make a case for changing how our industry talks about these documents, why “pointer” is a more accurate term than the misleading “modern attachment,” and why that change in terminology should have a positive impact on how we approach discovery of this information. Later articles will discuss specific discovery challenges posed by “modern attachments,” from preservation through production, which depend in large part on which discovery tool or M365 licensing an organization is using. We also will identify emerging best practices and wrap up with a list of key takeaways. The authors recognize that “modern attachments” are not limited to M365 and are at issue in other enterprise platforms, like Slack, but given the prevalence of the platform, this article series will focus on M365.

What Are “Modern Attachments” and Why Should You Care?

Organizations deploying collaboration platforms with short messaging/chat functionality are likely to use “modern attachments.” For example, the M365 tenant can be configured such that when users share documents, the files themselves are not transmitted with the message; instead, users are able to send messages that include a link that points to documents stored elsewhere. Users in Outlook or Teams can send messages containing a link that points to content stored in a separate location within the same M365 tenant, often in SharePoint or OneDrive. Storing the document separately from the message allows for ongoing collaboration among multiple users while eliminating the need for continually circulating many duplicate versions of a file.

Microsoft generally refers to the referenced content as “modern attachments” or sometimes “cloud attachments,” while others in the industry may refer to these as “linked files” or simply “attachments.” Unlike traditional email file attachments that are saved within the email .msg container with the associated message body and metadata, the files referenced in Outlook or Teams messages that are stored elsewhere may not be static. This means that the version of the file that is referenced from the sender’s message may have been edited or deleted when the recipient returns to the message and accesses the file, or may have been edited or deleted at a later time before the document is identified as subject to discovery.

Given the ubiquity of M365 and similar platforms, eDiscovery practitioners are grappling with whether the “as sent” version of the document that is referenced in the associated message can be retained, collected, reviewed, and/or produced for discovery purposes, and perhaps even more importantly, are asking: Does it need to be? Whether and how it can be depends on what M365 discovery tools and M365 licensing an organization is using and the functionality of those tools, which Microsoft is updating in real time. Answering the fundamental question of “Do we need to do this?” is more complex and requires a multi-faceted risk analysis specific to the organization and its litigation profile. We plan to explore these technical and legal challenges in future articles but first need to address the terminology surrounding these documents.

Pointers not Attachments

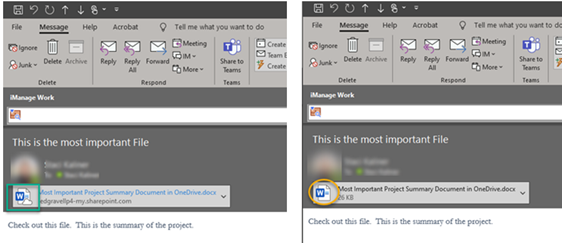

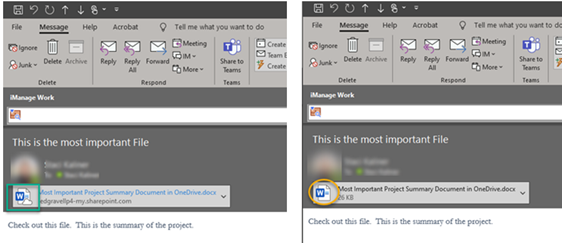

As noted above, Microsoft generally refers to documents stored in a separate location from the associated message as “modern attachments” or “cloud attachments,” but eDiscovery practitioners understand that these are not attachments at all; rather, they are links embedded in messages that reference files stored in the organization’s M365 cloud. (While users also can send messages that include a link that references files stored outside the client’s M365 cloud and/or outside the client’s IT infrastructure, those pointers are beyond the scope of this article series). These “modern attachments” may present to the user like any other more traditional file attachment. In Outlook, for example, the only visual difference between a traditional attachment and a “modern attachment” to the user is that a message with a “modern attachment” includes a cloud icon:

“Modern attachment” (left) vs. Traditional attachment

We posit that the term “pointer” is a far more apt description of the functionality here. Senders are pointing the recipient of the message to a location in the cloud where a specific document or file is stored. Pointers are one-directional, meaning the message references data stored in another source or location, but the source or location does not point back to the message. Stated simply, pointers are not attachments. Adopting the use of pointer for these documents may facilitate a more robust discussion within our industry as to whether it makes sense to treat the message and referenced content separately for discovery purposes. With this new terminology, we can develop meaningful strategies for defensible workflows, rather than simply defaulting to treating the message and referenced content like the traditional “parent/child” or “family” relationships that historically have been central to modern discovery practices. As we continue this series, we will use the terms “pointer” and “referenced content” and encourage others in the industry to join us in adopting this terminology going forward.

Authors’ Note: M365 is a cloud-based application that Microsoft is continually updating, which means the actual M365 functionality available in any tenant may differ from what is described in this article.

Staci Kaliner, Managing Director, routinely advises clients on the design and implementation of leading practice processes to support and reduce the eDiscovery related litigation risk, build efficacies into their operations, and identify and implement information governance best practices. She can be contacted at skaliner@redgravellp.com.

Monica McCarroll, Partner, is a trial attorney specializing in complex civil litigation and focuses her practice on providing advice and counsel on eDiscovery, information governance, and cybersecurity issues, including addressing the complicated discovery issues that often arise in litigation. She can be contacted at mmccarroll@redgravellp.com.

Ben Barnes, Counsel, has extensive experience in information law matters, and advises clients on eDiscovery, information governance, and data privacy issues and strategies.

The view and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of either Redgrave LLP or any client of the Firm.